Introduction In the annals of global health crises, few events compare to the 1918 Influenza Pandemic, often referred to as the Spanish Flu. O

Introduction

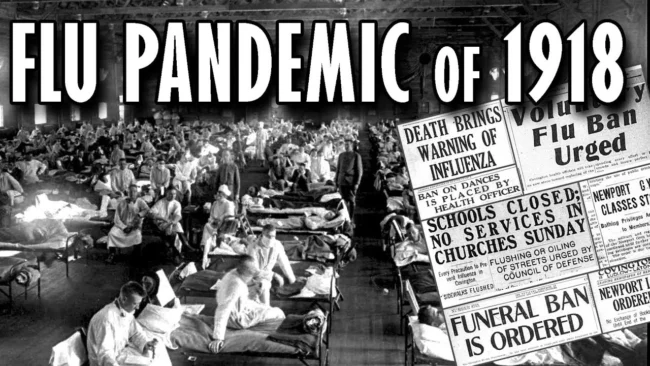

In the annals of global health crises, few events compare to the 1918 Influenza Pandemic, often referred to as the Spanish Flu. Occurring in the final year of World War I, this pandemic spread across continents with alarming speed and severity. Unlike any flu outbreak before or since, the 1918 pandemic caused massive global disruption, decimating populations, overwhelming healthcare systems, and leaving a legacy that continues to shape public health policies to this day.

Must visit: tradeinfinite

Estimated to have infected 500 million people—about one-third of the world’s population at the time—and to have caused between 20 and 50 million deaths, the 1918 pandemic was more lethal than even the war it coincided with. In this article, we will explore its origins, symptoms, mortality patterns, public responses, and long-term consequences on medicine and society.

The Mystery of the Virus’s Origin

Unlike many historical pandemics, the 1918 influenza did not begin in one clearly identified location. Multiple theories exist regarding its origin:

- One hypothesis suggests it began in Haskell County, Kansas, where soldiers training at Camp Funston in March 1918 began falling ill with flu-like symptoms.

- Others argue it may have originated in France, China, or even the United Kingdom, based on troop movements and earlier records of influenza outbreaks.

Despite its common name, “Spanish Flu,” the virus did not originate in Spain. The term arose because Spanish newspapers, not under wartime censorship, were the first to report openly on the outbreak. In contrast, Allied and Central Powers kept news of the outbreak quiet to avoid affecting military morale.

The Virus: H1N1 with Avian Origins

Modern research has identified the virus as a type of H1N1 influenza A virus with avian genetic components. What set it apart was its unusual virulence and the demographics it affected.

Most flu strains tend to be most dangerous to the very young and very old. The 1918 virus, however, displayed an unusual W-shaped mortality curve—killing not just infants and the elderly but also large numbers of healthy adults aged 20 to 40.

Scientists believe this was due to “cytokine storms,” or overly aggressive immune responses that caused inflammation and severe lung damage in younger individuals with robust immune systems.

The Pandemic’s Progression: Three Waves of Death

The 1918 pandemic did not consist of a single outbreak but rather occurred in three major waves:

First Wave – Spring 1918

The initial wave began in March 1918. It spread quickly among military populations and then to civilians. Though highly contagious, this version of the virus caused relatively mild symptoms and had a low mortality rate.

Second Wave – Autumn 1918

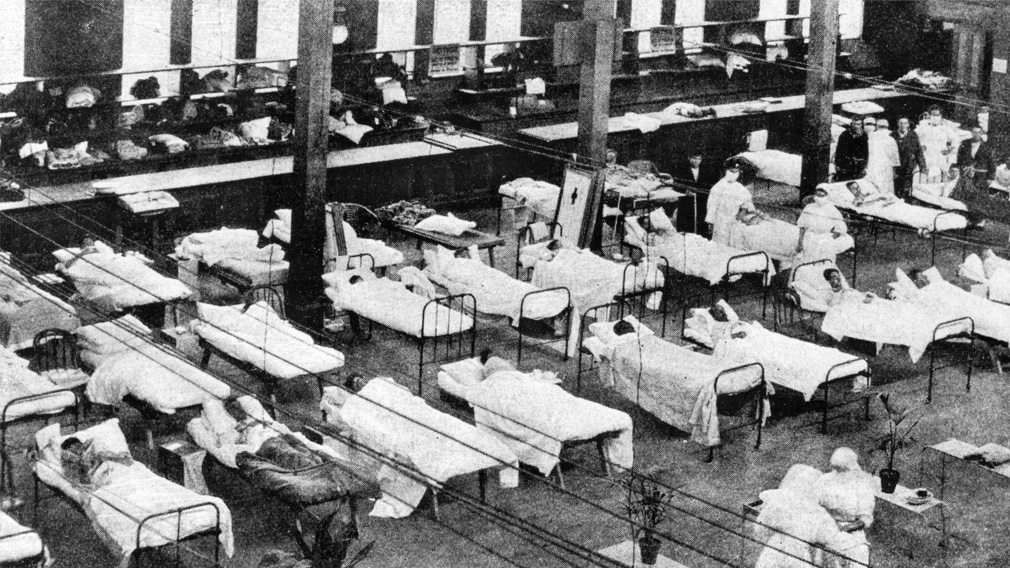

The second wave was devastating. Beginning in August 1918 and lasting through December, this mutated form of the virus became far more lethal. Victims often developed pneumonia-like complications, and death could occur within days—or even hours—of symptom onset. Entire families were wiped out, hospitals were overwhelmed, and coffins were in short supply.

Third Wave – Winter 1918 to Spring 1919

The final wave came in early 1919. It was less deadly than the second wave but still caused substantial illness and death. By the summer of 1919, the pandemic had largely ended, though some areas continued to report cases for months afterward.

Global Spread and Devastation

The flu reached virtually every corner of the globe, from dense cities to isolated Pacific islands. Its spread was facilitated by:

- Troop movements during and after World War I

- Global trade and travel via rail and ship

- Urban overcrowding and poor sanitation in many regions

Countries hit especially hard included:

- India, which saw more than 10 million deaths

- The United States, which lost approximately 675,000 lives

- Brazil, where entire towns suffered population collapse

- Iran, which reportedly lost up to 22% of its population

Some remote indigenous populations, such as the Inuits in Alaska and Pacific Islanders, lost as much as 30% to 40% of their populations due to lack of previous exposure to influenza viruses.

Symptoms and Clinical Presentation

The 1918 influenza was initially mistaken for a typical seasonal flu, but its symptoms were far more severe and included:

- High fever and chills

- Severe headaches

- Muscle and joint pain

- Coughing, often with blood (hemoptysis)

- Rapid onset of pneumonia

- Cyanosis (skin turning blue due to lack of oxygen)

- Respiratory failure and death within days

Autopsies often revealed lungs filled with fluid or hemorrhaged, giving them a dark, heavy appearance—described by some doctors as “melted red meat.”

Public Health Measures and Government Response

In the absence of vaccines or antiviral drugs, authorities relied on non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs). Responses varied widely from city to city and country to country.

Common Strategies:

- Quarantines and restrictions on movement

- Closure of schools, churches, bars, theaters, and other public venues

- Face mask mandates (often made from gauze or cloth)

- Promotion of hand hygiene and cough etiquette

- Public health posters and education campaigns

Cities like St. Louis implemented early and aggressive measures, which helped reduce their death toll. Others, like Philadelphia, held public events despite warnings and paid a heavy price in terms of lives lost.

Despite best efforts, the virus often outpaced the response. The sheer number of cases overwhelmed hospitals and mortuaries, and in some cities, mass graves were dug to cope with the influx of bodies.

Social and Psychological Effects

The pandemic deeply affected everyday life. People wore masks in public, social interaction was limited, and fear pervaded communities.

In some areas:

- Newspapers printed daily death counts

- Funerals were held with no attendees or clergy

- Orphans filled city-run homes

- Entire households died within days

The emotional toll was profound. Survivors described it as living through a silent war—without bombs but with invisible devastation.

Economic Impact

The economic impact was significant but varied depending on location and industry. In many cities:

- Businesses shut down due to worker illness

- Transportation systems stalled

- Agriculture and food production slowed dramatically

- Governments incurred increased public health spending

However, because the pandemic was relatively short-lived, most economies recovered within a few years—though at the cost of deep personal and communal suffering.

Medical and Scientific Legacy

The 1918 pandemic spurred major advancements in medicine and public health. Among the key outcomes:

1. Creation of National Health Agencies

Countries began investing in centralized health services and disease tracking systems to monitor and respond to future outbreaks.

2. Development of Influenza Vaccines

Although the virus wasn’t isolated until the 1930s, the pandemic led to significant investment in influenza research. By the 1940s, the first flu vaccines were developed.

3. Establishment of the World Health Organization

While WHO wasn’t created until 1948, the need for global coordination in health matters was clearly established during and after the 1918 pandemic.

4. Improved Hospital Infrastructure

The pandemic revealed the need for more hospitals, better training for nurses and doctors, and stockpiles of medical supplies.

Comparisons to Modern Pandemics

The 1918 influenza pandemic is often compared to modern outbreaks such as:

- 2009 H1N1 Influenza

- COVID-19 (2019–2024)

Although these newer pandemics caused substantial loss of life and social disruption, none matched the raw scale of 1918 in terms of global mortality.

However, today we benefit from:

- Rapid genomic sequencing

- Vaccines and antivirals

- Real-time global data sharing

- Stronger international collaboration

Still, the 1918 pandemic serves as a reminder that nature often works faster than science—and that preparedness is essential.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why was the 1918 flu so deadly compared to other flu viruses?

The 1918 flu was caused by a novel H1N1 virus to which humans had no prior immunity. It triggered severe immune responses, especially in young adults, leading to fatal complications like pneumonia and respiratory failure.

Q2: Why is it called the “Spanish Flu”?

Spain, being neutral during World War I, was one of the first countries to openly report on the outbreak. This gave the false impression that the virus originated there, leading to the nickname.

Q3: How many people died during the 1918 pandemic?

Estimates vary, but most scholars agree that between 20 million and 50 million people died, with some studies suggesting as many as 100 million fatalities globally.

Q4: Was there a vaccine for the 1918 flu?

No. Vaccines for influenza were not developed until the 1940s. At the time, treatments were limited to supportive care like hydration and rest.

Q5: Why did the 1918 flu affect young adults so severely?

The virus triggered an intense immune response known as a cytokine storm in many healthy young adults, leading to severe lung damage and death.

Q6: How long did the 1918 pandemic last?

The pandemic lasted from early 1918 to mid-1919, with three major waves occurring over roughly 15 months.

Q7: Did public health measures work?

Yes and no. In cities where interventions were implemented quickly and maintained, death rates were significantly lower. Delayed or inconsistent responses led to much higher fatalities.

Q8: Could something like the 1918 pandemic happen again?

Yes. New influenza strains continue to emerge, and pandemics remain a global threat. However, modern medicine and surveillance systems offer better tools to manage outbreaks.

Conclusion

The 1918 Influenza Pandemic was more than just a health crisis—it was a transformative global event that reshaped medicine, society, and our understanding of infectious disease. Its legacy is reflected in the health systems, scientific institutions, and international collaborations we rely on today.

Even over a century later, its lessons remain vivid: pandemics demand vigilance, speed, science, and solidarity. And while we cannot predict every threat, remembering 1918 reminds us why preparation matters.

COMMENTS